Tungsten metal possesses outstanding properties such as high melting point, high density, high strength, high hardness, low sputtering rate, and high electrical conductivity, making it widely used in aerospace, nuclear industry, electronics, and other fields [1]. However, tungsten exhibits poor plasticity at room temperature, prone to cracking during processing, and has poor machinability. Additionally, recrystallization occurs above 1150°C, causing grain coarsening and re-segregation of impurity elements (such as O and P) at grain boundaries, thereby reducing intergranular bonding strength. Simultaneously, recrystallization generates numerous disordered new grains [2], whose fragile grain boundaries trigger recrystallization brittleness, leading to reduced material strength and elevated ductile-to-brittle transition temperatures [3–4].

Rhenium exhibits both a high melting point and elastic modulus, with no distinct ductile-to-brittle transition temperature. Adding rhenium to tungsten weakens the dislocation slip resistance (Pinner force), enhances dislocation mobility, and improves lateral slip and climb capabilities, thereby improving tungsten's plasticity. Furthermore, rhenium's solid solution effect reduces stacking fault energy in tungsten, promoting twinning formation. This accelerates slip system motion under external forces, enhancing the material's plastic deformation capacity. Rhenium addition lowers tungsten's ductile-to-brittle transition temperature while raising its recrystallization temperature [5–6]. To enhance tungsten's thermal stability, strengthening solely through rhenium is insufficient. An effective reinforcement method involves dispersing small amounts of He bubbles, K bubbles, or thermally stable carbide or oxide nanoparticles (e.g., La₂O₃, Y₂O₃, HfC, and ZrC) within the tungsten matrix [7–16]. These nanoparticles dispersed at grain boundaries pin grain boundaries and dislocations by increasing migration energy, thereby suppressing their motion [17–20]. This stabilizes the microstructure and prevents grain growth even at elevated temperatures. Miao et al. [21] prepared W-10Re-0.5ZrC alloy via high-energy ball milling and discharge plasma sintering, achieving an ultimate tensile strength of 818 MPa and elongation of 8.1% at 300°C. Research indicates that the solid solution of rhenium reduces the driving force for grain coarsening, while uniformly distributed nano-ZrC particles within grains and at grain boundaries pin dislocations and restrict grain boundary mobility, enhancing alloy strength. Li et al. [22] prepared W-3Re-xHfC alloys with varying HfC contents via discharge plasma technology. The study revealed spherical HfC nanoparticles and micrometer-scale clusters distributed at grain boundaries within the W-Re matrix. These nanoscale HfC particles pin dislocations and grain boundaries while refining grain size, thereby enhancing the composite's strength. The higher the melting point of the second phase, the higher its recrystallization temperature and stability at elevated temperatures. ZrC has a melting point of 3540°C, TiC at 3160°C, and HfC at 3890°C. Thus, carbides with higher melting points hold greater promise than oxides for improving tungsten's high-temperature properties.

This study prepared tungsten-rhenium alloys reinforced with metal carbides via conventional uniaxial sintering. It comparatively analyzed the strengthening effects of different metal carbides (ZrC, TiC, HfC) on the tungsten-rhenium matrix and their underlying mechanisms.

1 Experimental Materials and Methods

The raw materials used in the experiments were industrial tungsten powder (purity 99.99%, particle size approximately 1 μm), rhenium powder (purity 99.99%, particle size approximately 5 μm), zirconium carbide powder (purity 99%, particle size approximately 50 nm), titanium carbide powder (purity 99%, particle size approximately

50 nm), and hafnium carbide powder (purity 99%, particle size approximately 800 nm). The tungsten-rhenium alloy (W—4Re, mass fraction) without added metal carbide second phases was designated WR. Tungsten-rhenium alloys containing 0.8% mass fraction of metal carbides (ZrC, TiC, HfC) were designated WR—ZrC, WR—TiC, and WR—HfC, respectively.

W powder, Re powder, and metal carbide powders (ZrC, TiC, HfC) were mixed in predetermined ratios and loaded into a 100 mL mixing bottle. Zirconia balls (ϕ5 mm) were added at a ball-to-powder ratio of 3:1. The mixture was ground in a jar mill for 12 hours to ensure thorough blending. After mixing, the powder was transferred into a 42 mm × 15 mm × 8 mm hardened steel mold, compacted at 100 MPa, held at pressure for 2 minutes, then demolded. The compacted green bodies were placed in a high-temperature sintering furnace for sintering under hydrogen atmosphere. During sintering, hold at 1100°C for 2 hours for pre-sintering, followed by holding at 1900°C for 2 hours for final densification.

The DahoMeter DE-120M density meter was used to measure material density. The Vickers hardness of the materials was tested using the Shanghai Lianer Testing Equipment Co., Ltd. (Shanghai Lianer) HVS-1000 digital microhardness tester with a load of 1.0 kg applied for 10 seconds. To minimize experimental error, each material was tested 20 times, and the average value was taken. Tensile and compression specimens were cut using a wire-cut machine. Tensile specimens underwent room-temperature tensile testing on a Sinotest DDL300 universal testing machine at a displacement rate of 0.6 mm·min⁻¹. Compression specimens underwent high-temperature compression testing at 1200°C on a Gleeble-3180 thermal simulation testing machine at a strain rate of 1 s⁻¹.

Phase analysis of the powder and sintered green bodies was performed using a Rigaku TTRIII X-ray diffractometer (XRD). Surface and tensile fracture morphologies were observed using a MIRA4LMH scanning electron microscope (SEM), with the size of 200 randomly selected grains statistically analyzed. After thinning with a Gatan 695 ion mill, microstructures were examined using a Tecnai G2F20 transmission electron microscope (TEM).

2 Results and Discussion

2.1 Phase Composition and Microstructure

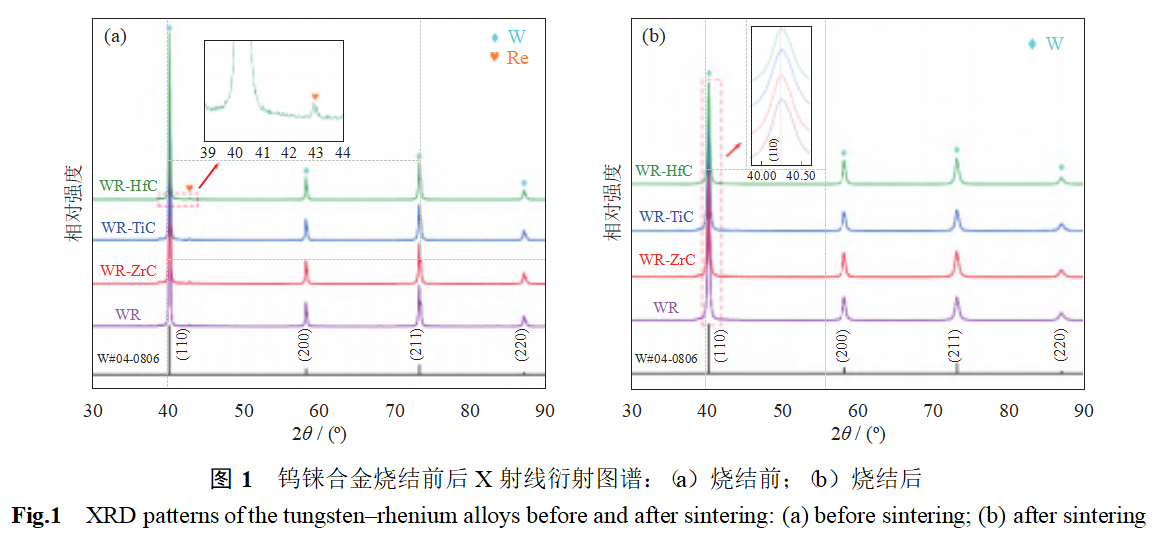

Figure 1 shows the X-ray diffraction patterns of different tungsten-rhenium alloys before and after sintering. As seen in Figure 1, all four diffraction peaks of the tungsten-rhenium alloys before and after sintering correspond to the (110), (200), (211), and (220) crystal planes in the W standard card (#04-0806). Additionally, all tungsten-rhenium alloys exhibit a diffraction peak corresponding to the Re(101) crystal plane before sintering, which disappears after sintering. This indicates that Re atoms solid-solve into the W lattice during the sintering process. After sintering, the diffraction peaks of the (110) crystal plane in each tungsten-rhenium alloy shifted toward higher angles. The angle of the WR(110) crystal plane diffraction peak changed from 40.260° before sintering to 40.272° after sintering. Concurrently, the lattice parameter decreased from 0.31660 nm before sintering to 0.31636 nm after sintering, indicating lattice contraction [23]. This reduction in lattice parameter resulted from the replacement of larger W atoms (0.193 nm) in the W lattice by smaller Re atoms (0.188 nm). No diffraction peaks of secondary phase metallic carbides were observed in any of the WR alloys before or after sintering. This is primarily attributed to the low addition amount, which fell below the detection limit and could not be detected.

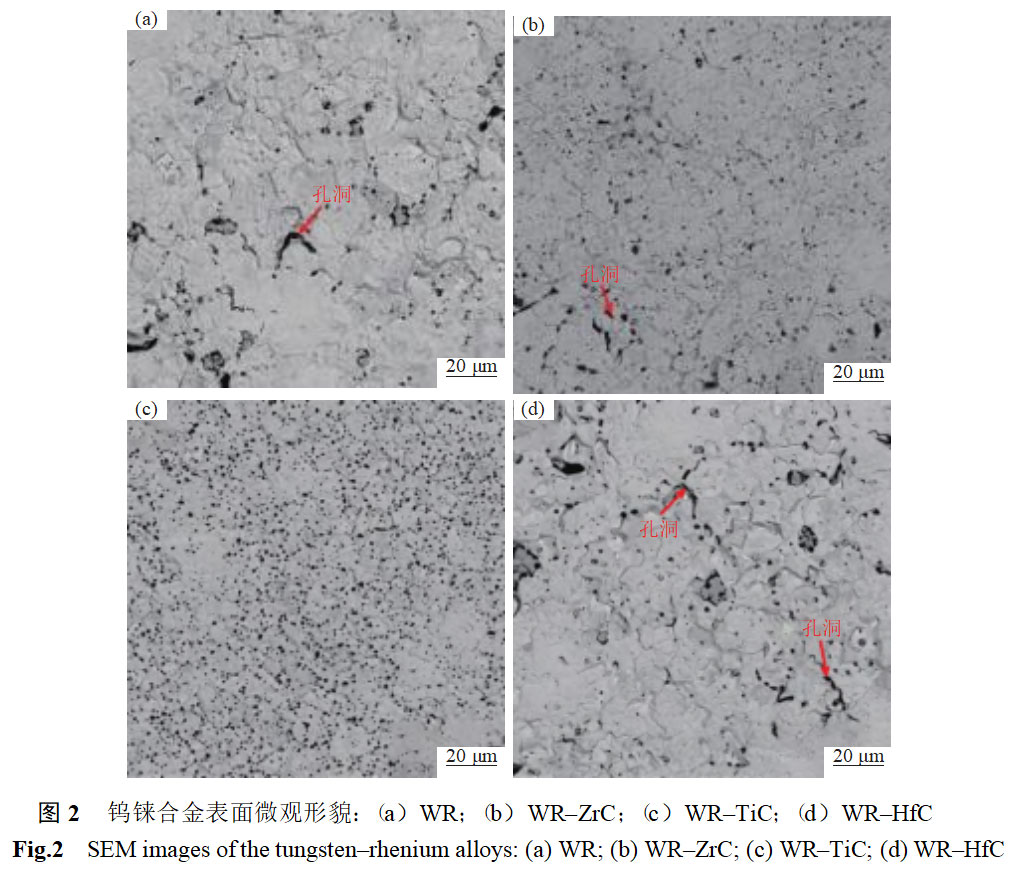

The surface microstructure of sintered WR specimens is shown in Figure 2. As indicated by the arrows, WR exhibits significant porosity. Following the addition of refractory carbides, porosity decreased relatively, with WR–TiC showing no visible pores. This demonstrates that the second-phase refractory carbides enhance the relative density of WR alloys. Indeed, the relative density of WR measured by the displacement method was 92.52%, while WR–ZrC, WR–TiC, and WR–HfC exhibited densities of 94.15%, 96.77%, and 93.17%, respectively.

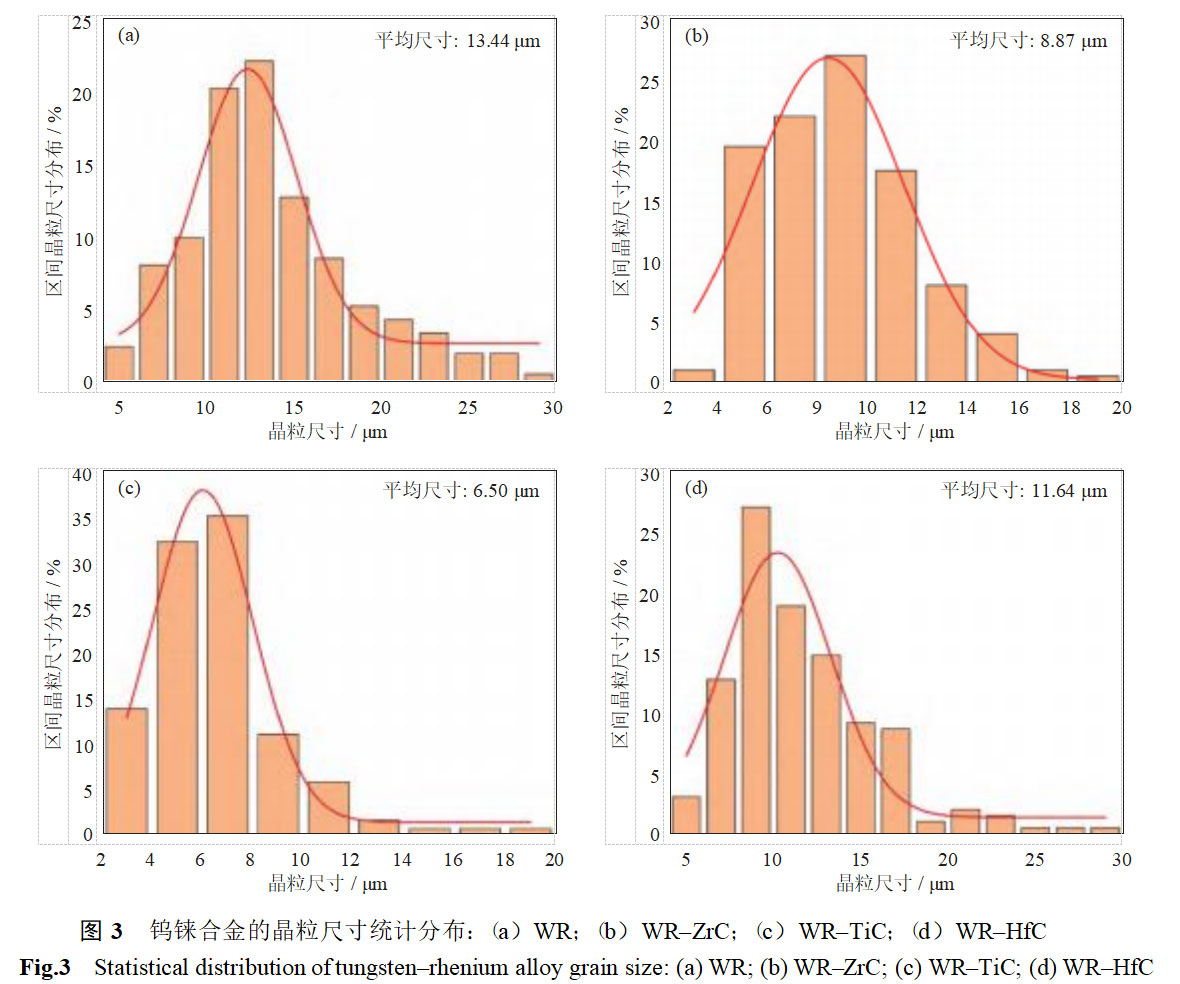

The average grain size of the tungsten-rhenium alloy was calculated by statistically analyzing the grain size based on the surface morphology of the alloy, as shown in Figure 3. The average grain size of WR was 13.44 μm, while WR–ZrC, WR–TiC, and WR–HfC exhibited average grain sizes of 8.87 μm, 6.50 μm, and 11.64 μm, respectively. Compared to WR, these values decreased by approximately 34%, 52%, and 13%. The addition of 0.8 wt% refractory carbide second phases refined the grain structure of the tungsten-rhenium alloy. This indicates that during high-temperature sintering, ZrC, TiC, and HfC particles all inhibit grain growth in the tungsten-rhenium matrix, with TiC exhibiting the most pronounced refining effect. As shown in Figure 3(c), the WR–TiC alloy exhibits a narrower grain size distribution, with the majority ranging from 4.00 to 8.00 μm. This indicates a more uniform grain size distribution in WR–TiC, which reduces stress concentration during deformation and enhances the plastic deformation capability of the alloy.

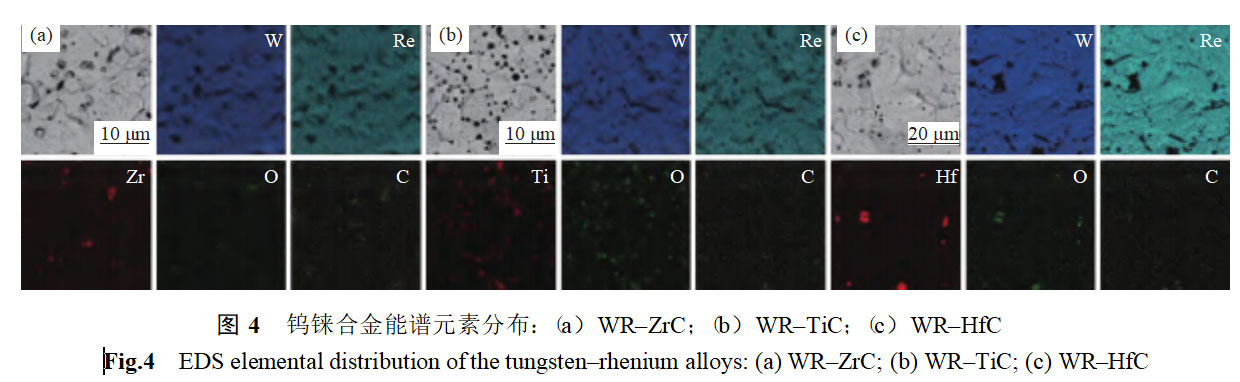

Figure 4 shows the energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) elemental distribution of WR–ZrC, WR–TiC, and WR–HfC. As shown in Figure 4, the distribution of Re atoms completely overlaps with that of W atoms, further confirming that Re has fully solid-solved into W after 2 hours of holding at 1900°C. The solid solution of Re induces lattice distortion, reducing the dispersion of W at high temperatures. This effectively delays the nucleation of W grains and inhibits recrystallization [11]. In WR–TiC alloys, the distribution of O largely coincides with that of Ti, but C clusters exclusively at Ti sites. This indicates that part of the TiC has transformed into TiO₂ [24-25]. This occurs because TiC captures impurity O at grain boundaries, reducing O enrichment, purifying grain boundaries, thereby enhancing the bonding strength of W grain boundaries and improving the performance of tungsten-rhenium alloys. Similar phenomena occur in WR–ZrC and WR–HfC [26‒27], where Zr, Hf, and O respectively form ZrO₂ and HfO₂. Since the refractory carbide second phases are added at identical mass ratios, and TiC exhibits the lowest density among these three refractory carbides (densities of TiC, ZrC, and HfC are 4.93 g·cm^(−3), 6.73 g·cm⁻³, and 12.70 g·cm⁻³), the volume fraction of TiC is the highest among the three added refractory carbide second phases. This explains the greater quantity of second phases in WR–TiC, where more uniformly distributed TiC particles contribute to enhanced strengthening effects.

2.2 Mechanical Properties

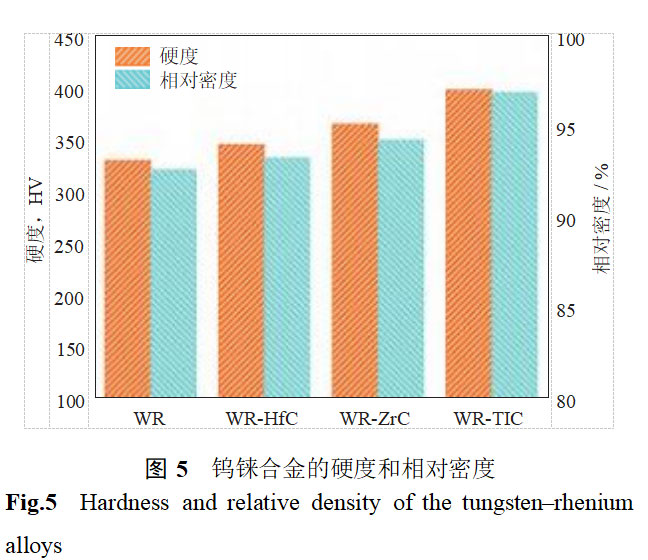

Figure 5 shows the hardness and relative density of tungsten-rhenium alloys with different types of refractory carbides added. As shown, the relative density and hardness of the tungsten-rhenium alloys increase to varying degrees with the addition of the second-phase refractory carbides. The hardness and relative density of WR are HV328.17 and 92.52%, respectively. WR–HfC exhibits hardness and relative density of HV343.31 and 93.17%, respectively, representing approximately 5% and 0.65% increases over WR. WR–ZrC shows hardness and relative density of HV363.08 and 94.15%, respectively, indicating approximately 11% and 1.63% improvements over WR. WR–TiC exhibits the highest hardness and relative density at HV396.1 and 96.77%, respectively, representing increases of approximately 21% and 4.25% over WR. During the final sintering stage, the relative density of the alloy is determined by the disparity between grain boundary diffusion and migration rates. If grain boundary migration is rapid, voids at grain boundaries readily detach from the boundaries, forming isolated voids within grains. These isolated voids are difficult to eliminate during sintering, resulting in low alloy relative density. Conversely, if grain boundary diffusion is slow, voids at grain boundaries can be expelled along the boundaries, thereby enhancing alloy relative density [28‒29]. In tungsten-rhenium alloys, the addition of refractory carbides pins the grain boundary migration, slowing its rate. Consequently, the relative density of the tungsten-rhenium alloy increases. The enhancement in alloy hardness stems from grain refinement. As grain size decreases, the grain boundary area increases, thereby strengthening the material's resistance to deformation and fracture, ultimately improving its hardness.

Figure 6 shows the engineering stress–strain curves, tensile strength, and elongation of different tungsten-rhenium alloys at room temperature. As depicted in Figure 6, the elongation and ultimate tensile strength of WR are 2.82% and 141 MPa, respectively. The addition of refractory carbide second phases enhances both elongation and ultimate tensile strength to varying degrees. WR–HfC exhibits an elongation of 2.90% and a tensile strength of 180 MPa, representing increases of 0.08% and 28%, respectively, compared to WR. WR–ZrC exhibits an elongation of 3.30% and a tensile strength of 226 MPa, representing increases of 0.48% and 60% over WR; WR–TiC demonstrates an elongation of 3.50% and a tensile strength of 233 MPa, showing improvements of 0.68% and 65% compared to WR.

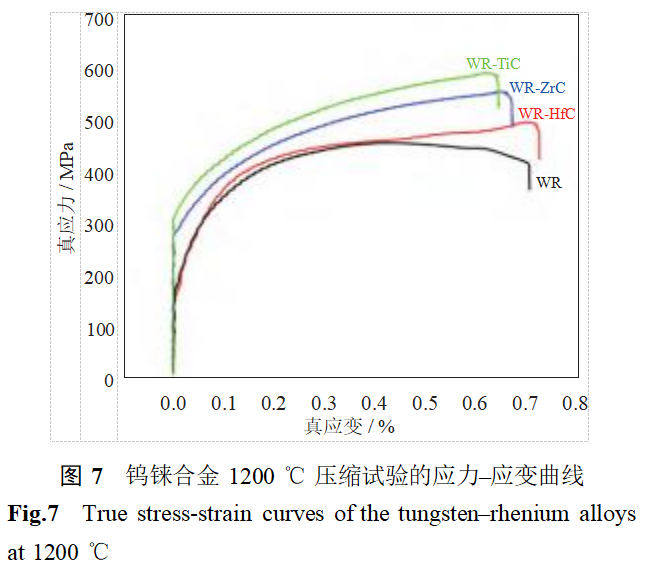

The true stress-strain curves of tungsten-rhenium alloys during high-temperature compression testing at 1200°C are shown in Figure 7. As depicted in Figure 7, WR exhibits the lowest compressive strength at 440 MPa. The addition of HfC, ZrC, and TiC all enhances the compressive strength of the tungsten-rhenium alloys. Specifically, WR–HfC exhibits a compressive strength of 490 MPa, representing an 11% increase over WR; WR–ZrC achieves 548 MPa, a 25% improvement over WR; and WR–TiC demonstrates the highest compressive strength at 585 MPa, a 33% increase over WR.

2.3 Fracture Mechanism and Strengthening Mechanism

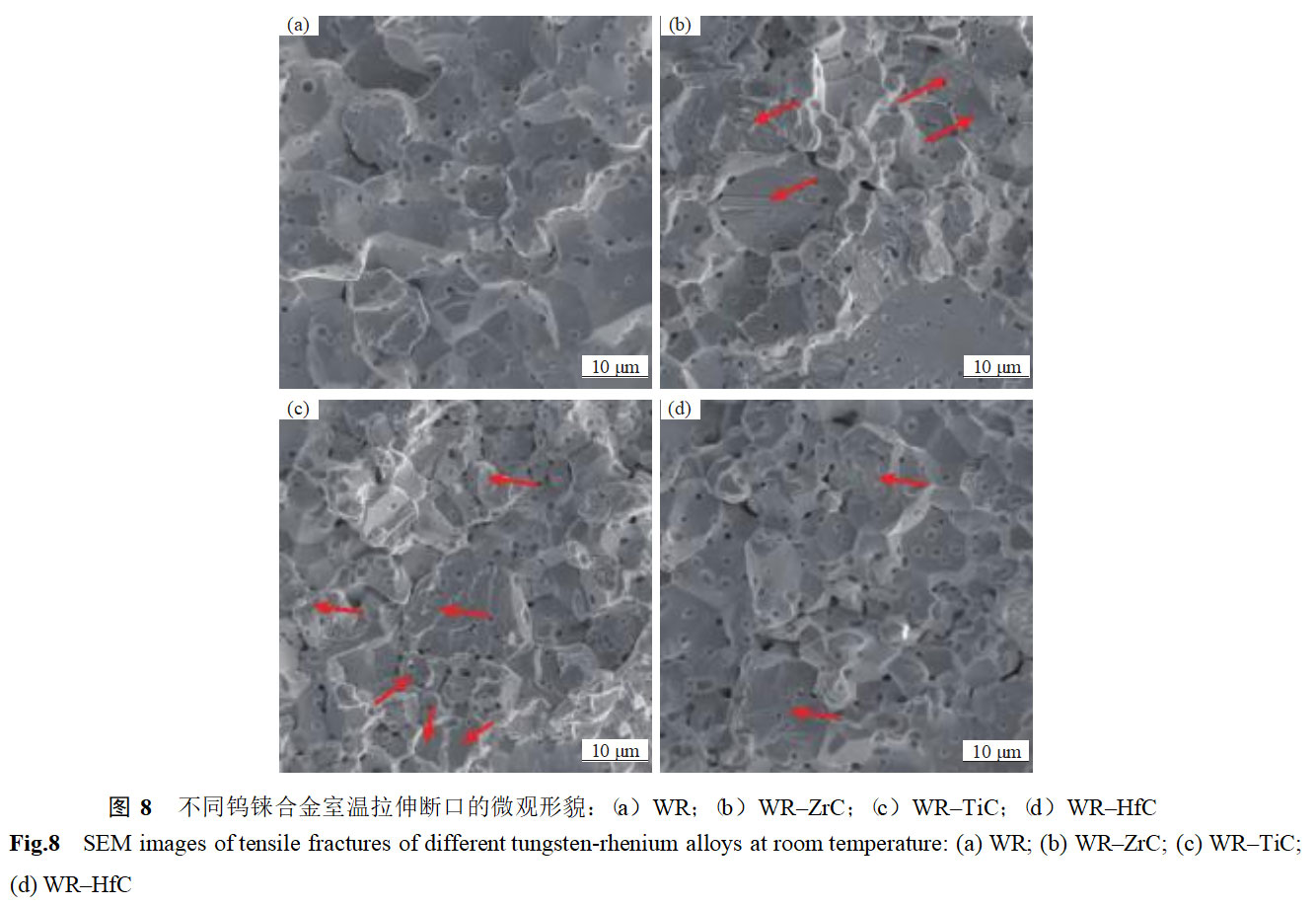

To analyze the microstructural mechanism of tensile fracture behavior, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) characterization was performed on the fracture surfaces of each tungsten-rhenium alloy after tensile testing. The results are shown in Figure 8. As seen in Figure 8, all tungsten-rhenium alloys exhibited brittle fracture behavior, with no ductile fracture features such as ductile pits. The WR fracture surface consists entirely of rock-candy-like intergranular fracture without any deformed microstructure, indicating poor bonding at grain boundaries. This leads to crack propagation along grain boundaries during plastic deformation, resulting in intergranular fracture. The fracture surfaces of WR–ZrC, WR–TiC, and WR–HfC exhibit a certain amount of river-patterned transgranular fracture, demonstrating that the addition of refractory carbide second phases enhances the interfacial bonding strength at W grain boundaries. High-hardness reinforcing particles deflect crack propagation paths, rendering them tortuous. More tortuous crack paths consume greater crack propagation energy, resulting in higher fracture toughness [26]. The addition of refractory carbide second phases transforms the fracture mode of the tungsten-rhenium matrix from intergranular to transgranular fracture, thereby enhancing the material's plasticity.

The fracture strength (δf) of tungsten alloys is microscopically related to the intergranular fracture strength (δw), the transgranular fracture strength (δw-w), the stress distribution non-uniformity caused by differences in the two-phase microstructure, and the triaxial stress state (δ0), and can be expressed by Equation (1).

δf = fwδw + fw-wδw-w + δ0 (1)

Where: fw is the percentage of intergranular fracture in tungsten grains, %; fw-w is the percentage of transgranular fracture in tungsten grains, %.

For tungsten-based materials, the intergranular fracture strength of tungsten grains is significantly greater than their intergranular fracture strength. Therefore, the greater the number of grains fracturing intergranularly, the higher the strength of the tungsten-based material. Fracture morphology reveals that the addition of refractory carbide second phases induces more intergranular fracture. Among the tungsten-reumium alloys, the intergranular fracture proportions decrease in the order WR–TiC, WR–ZrC, WR–HfC, WR. Consequently, WR–TiC exhibits the highest strength among these four alloys, while WR alloy shows almost no intergranular fracture and thus the lowest strength.

In powder metallurgy, relative density is enhanced through optimized sintering methods and subsequent machining. However, sintered materials inevitably retain some porosity. In tungsten-based materials, while these pores do not cause significant stress concentration, they induce crack initiation and propagation, reducing the material's elongation. In tensile tests, WR fractured at a strain of 2.8%, whereas WR–HfC, WR–ZrC, and WR–TiC fractured at 2.9%, 3.3%, and 3.5% strain, respectively. The incorporation of HfC, ZrC, and TiC increases the relative density of the tungsten-rhenium alloy. This reduction in porosity mitigates stress concentration at grain boundaries during deformation, thereby enhancing the plasticity of the tungsten-rhenium matrix. During deformation, the increased relative density enables the material to withstand greater loads, consequently improving its strength.

Grain refinement plays a crucial role in enhancing the strength and ductility of tungsten-rhenium matrixes. According to the Hall-Petch relationship, grain refinement introduces numerous grain boundaries that impede dislocation motion and propagation to adjacent grains, thereby increasing material strength. The poor plasticity of tungsten-based materials at room temperature primarily stems from tungsten's high sensitivity to soluble interstitial elements (such as C, O, N, etc.) that segregate at grain boundaries [30–32]. When grains are refined, the increased number of grain boundaries dilutes the concentration of these impurity elements, thereby improving the plasticity of tungsten-based materials. Within a given volume, finer grains increase the number of grains, thereby increasing the number of grains aligned in the preferred slip direction during deformation. Deformation is distributed across more grains, reducing stress concentration and promoting more uniform deformation. Additionally, smaller grain sizes result in more distorted grain boundaries, lowering the likelihood of cracking during plastic deformation and effectively inhibiting crack propagation [32]. Consequently, WR–HfC, WR–ZrC, and WR–TiC exhibit greater elongation than WR.

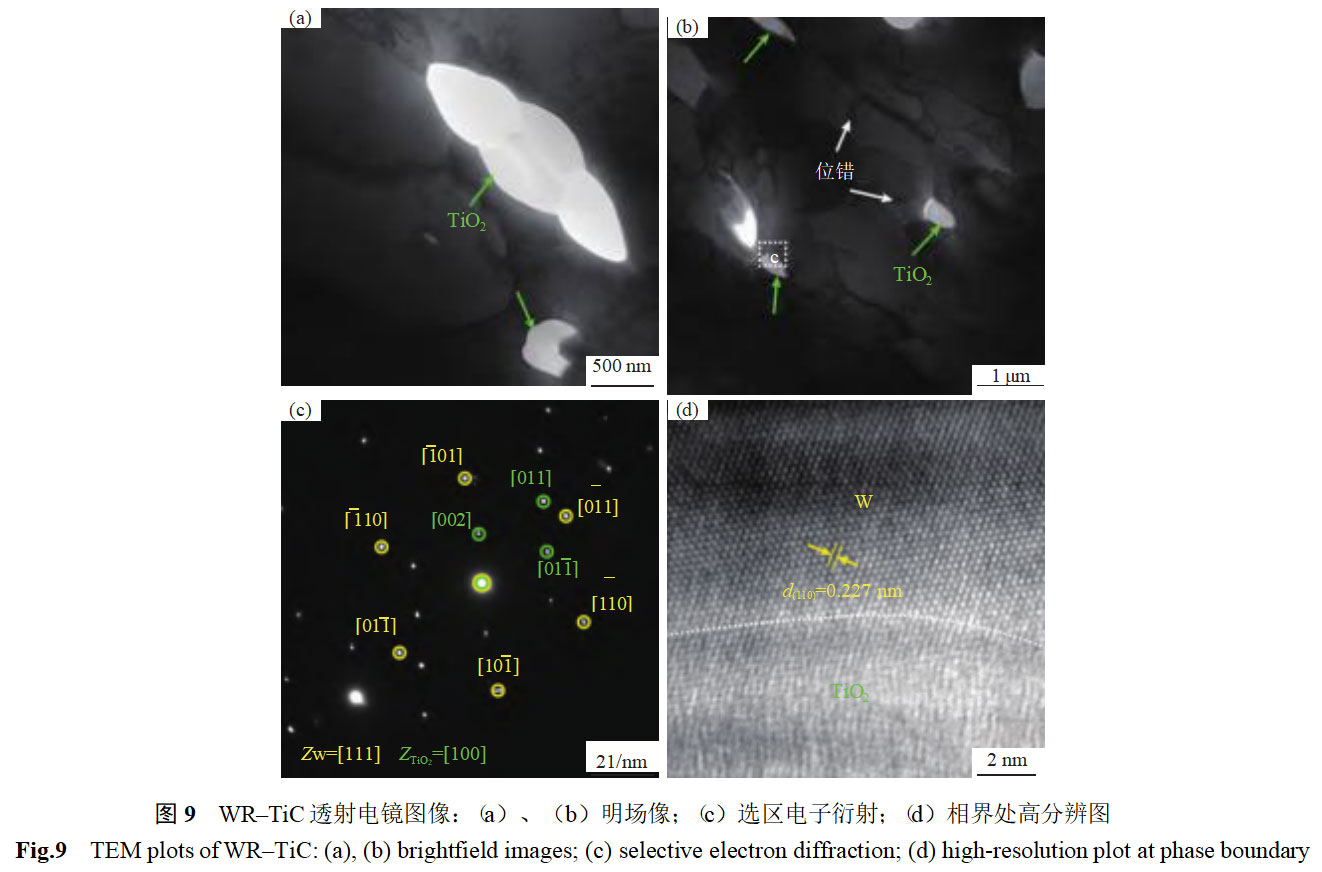

Figure 9 shows the transmission electron microscopy morphology of WR–TiC after high-temperature compression. The enhancement of strength in tungsten-rhenium alloys by second-phase refractory carbides primarily stems from two mechanisms. First, the doped second-phase refractory carbide particles adsorb oxygen impurities within the powder, strengthening intergranular bonding. They form oxide particles that impede grain growth and inhibit intergranular movement, as indicated by the dark arrows in Figures 9(a) and 9(b). When dislocations migrate to grain boundaries, they accumulate, forming dislocation pileups. Fine grains reduce dislocation density near grain boundaries, lessen stress concentration, and increase the difficulty of activating dislocation sources in adjacent grains. This makes plastic deformation of the tungsten-rhenium alloy difficult, thereby enhancing its strength. Additionally, refractory carbide particles of the second phase, enclosed by grains and present around dislocations (indicated by light arrows in Figure 9(b)), impede dislocation motion and suppress deformation of the matrix, further enhancing its strength. During high-temperature compression testing, these refractory carbide particles exhibit excellent thermal stability and strong bonding capability at their interfaces with the W matrix, contributing to superior high-temperature strength. The selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern within the dashed box in Figure 9(b) is shown in Figure 9(c), revealing W phase diffraction spots with a [111] crystal zone axis. Concurrently, the TiO₂ phase exhibits a body-centered cubic structure with a [100] crystal zone axis. Figure 9(d) presents the high-resolution microstructure at the phase boundary within the dashed box in Figure 9(b). The upper portion of the boundary consists of the W matrix, with a measured interplanar spacing of 0.227 nm corresponding to the (110) plane of W. The lower portion comprises TiO₂ particles.

3 Conclusions

(1) The addition of refractory metal carbides ZrC, TiC, and HfC enhances the properties of tungsten-rhenium alloys. Among these, TiC exhibits the most significant strengthening effect on the alloy.

(2) The TiC-reinforced tungsten-rhenium alloy (WR–TiC) exhibits a relative density of 96.77%, hardness of HV 396.1, and room-temperature tensile strength of 233 MPa. Compared to the unmodified tungsten-rhenium alloy (WR), these properties improved by 4.25%, 21%, and 65%, respectively.

(3) The TiC-reinforced tungsten-rhenium alloy (WR–TiC) exhibits a compressive strength of 585 MPa at 1200°C, representing a 33% increase over the unmodified tungsten-rhenium alloy (WR).

(4) The enhanced alloy strength is primarily attributed to grain refinement strengthening and dispersion strengthening effects imparted by the refractory carbide second phase.

(5) The second-phase refractory carbides transformed the fracture mode of the tungsten-rhenium matrix from intergranular fracture to trans granular fracture, thereby enhancing ductility.

References: Original article link: https://libdb.csu.edu.cn/vpn/11/https/NNYHGLUDN3WXTLUPMW4A/kcms2/ article/abstract?v=dzw7IdLhHkGAw5UyX4rDEGOLcRddkRWwPywYX2SWVXmsVBYbFXo2O4pqaVwvO9rat7iupGRoxzc3lTEeYU2-JXJrppWmpl2k1w_wIG -FMWoMjEYZABCxfEPVcz4TE3lX-8J80IRVkeYIAyeL_lTe8wqrpY664-ekDJIVG_S_La2brBec2gIsPQ==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS

Vol. 43, No. 5, October 2025, Powder Metallurgy Technology; Preparation and Mechanical Properties of Metal Carbide-Reinforced Tungsten-Rhenium Alloys;

Guo Jianwei¹), Dong Di¹⁻²⁾✉, Wu Zhuangzhi³⁾, Chen Fuge¹⁾, Wu Haoyang²⁾, Liu Jie¹⁾

Stardust Technology (Guangdong) Co., Ltd. specializes in the R&D and production of high-end spherical metal powders for applications such as additive manufacturing (3D printing). The company offers various rare refractory metal powders, including spherical tungsten powder and spherical rhenium powder, and utilizes its core technology to produce tungsten-rhenium alloy powder. Its products are manufactured using radiofrequency plasma spheroidization technology, a process that yields powders with high sphericity, smooth surfaces, excellent flowability, and low impurity content. These high-performance spherical powders primarily serve sectors with stringent material requirements, such as high-temperature components in aerospace, medical implants, and the electronics industry. Leveraging national-level research platforms and an experienced technical team, the company focuses on meeting high-end manufacturing demands and participates in establishing relevant industry standards. For further product information, please contact our professional sales manager, Cathie Zheng, at +86 13318326187.