0 Introduction

In advanced aeroengines, high-temperature alloys account for 40%–60% of total material usage. Among these, nickel-based high-temperature alloys are the most widely used. GH738 alloy belongs to the γ′ phase precipitation-hardened high-temperature alloy family, exhibiting excellent resistance to combustion gas corrosion, high yield strength, superior fatigue properties, good machinability, and stable microstructure. It is extensively applied in hot-end components such as turbine casings and turbine discs, and other hot-end components [1-2]. GH738 alloy components are prone to failure modes such as fatigue cracking and wear when operating under severe conditions. Direct replacement with new components incurs high production costs; however, rapid repair of failed components not only significantly shortens maintenance cycles but also substantially reduces production costs [3].

Laser additive manufacturing integrates the rapid prototyping principle with laser cladding technology to form a rapid forming technique for producing high-performance dense metal parts [4]. Laser repair technology, rapidly evolving from laser additive manufacturing, serves as a responsive repair solution. It primarily addresses machining errors during production and in-service failures. By treating damaged components as specialized substrates, laser stereolithography restores original shapes through three-dimensional forming. Post-repair parts achieve composition, microstructure, and performance comparable to forgings—effectively creating new components [5-7]. demonstrating broad application prospects in the field of remanufacturing engineering.

After repairing GH738 alloy with matching powder and subsequent heat treatment, the hardness of the repaired zone exceeds that of the base material [8]. Due to the technical characteristics of laser repair forming, the strength of the repaired zone after using matching powder to repair GH738 alloy is higher than the base material, while its plasticity is lower, adversely affecting the comprehensive mechanical properties of the repaired part. By utilizing different alloy powders as raw materials and modifying the composition of the repair alloy based on the mechanical properties of the substrate, the mechanical properties of the repair zone can be matched to those of the substrate. This approach not only enhances the overall mechanical properties of the repaired part but also further increases the flexibility of laser repair technology for high-temperature alloys.

Similar to GH738 alloy, GH4169 alloy exhibits high strength at elevated temperatures, high creep resistance, and excellent high-temperature corrosion resistance. It is also applied in integral hot-end components of aero-engine systems [2,9]. Therefore, GH4169 alloy powder can be selected for rapid repair of damaged GH738 alloy components and those failing during service. By treating the damaged part as a special substrate and performing laser stereolithography according to the defect geometry, the original part shape can be restored. The composition, microstructure, and properties of the repaired part can still meet forging standards, effectively equivalent to repairing it into a new part [5-7], demonstrating broad application prospects in the field of remanufacturing engineering.

When repairing GH738 alloy with identical powder material followed by heat treatment, the hardness of the repaired zone exceeds that of the substrate [8]. Due to the technical characteristics of laser repair forming, the strength of the repaired zone after using identical powder material is higher than the substrate, while its plasticity is lower, adversely affecting the comprehensive mechanical properties of the repaired part. By using different alloy powders as raw materials and modifying the composition of the repair alloy based on the mechanical properties of the substrate, the mechanical properties of the repair zone can be matched to those of the substrate. This not only enhances the overall mechanical properties of the repaired part but also further increases the flexibility of laser repair technology for high-temperature alloys.

Similar to GH738 alloy, GH4169 alloy exhibits high strength at elevated temperatures, high creep resistance, and excellent high-temperature corrosion resistance, making it suitable for integral hot-end components in aeroengines [2,9]. Therefore, GH4169 alloy powder can be selected for repairing GH738 alloy. While domestic and international studies have explored GH536 alloy powder for repairing GH738 [10], research using GH4169 alloy powder for this purpose remains limited.

High-temperature alloy components are prone to failure modes such as wear and cracking during service, with high-temperature creep and fatigue performance metrics significantly impacting engine service life and operational capabilities. This study employs GH4169 alloy powder for laser repair of GH738 alloy specimens. The repaired specimens undergo solution treatment followed by dual aging heat treatment. In-depth investigations into high-temperature creep and low-cycle fatigue performance are conducted to establish a foundation for dissimilar material repair.

1. Experiment

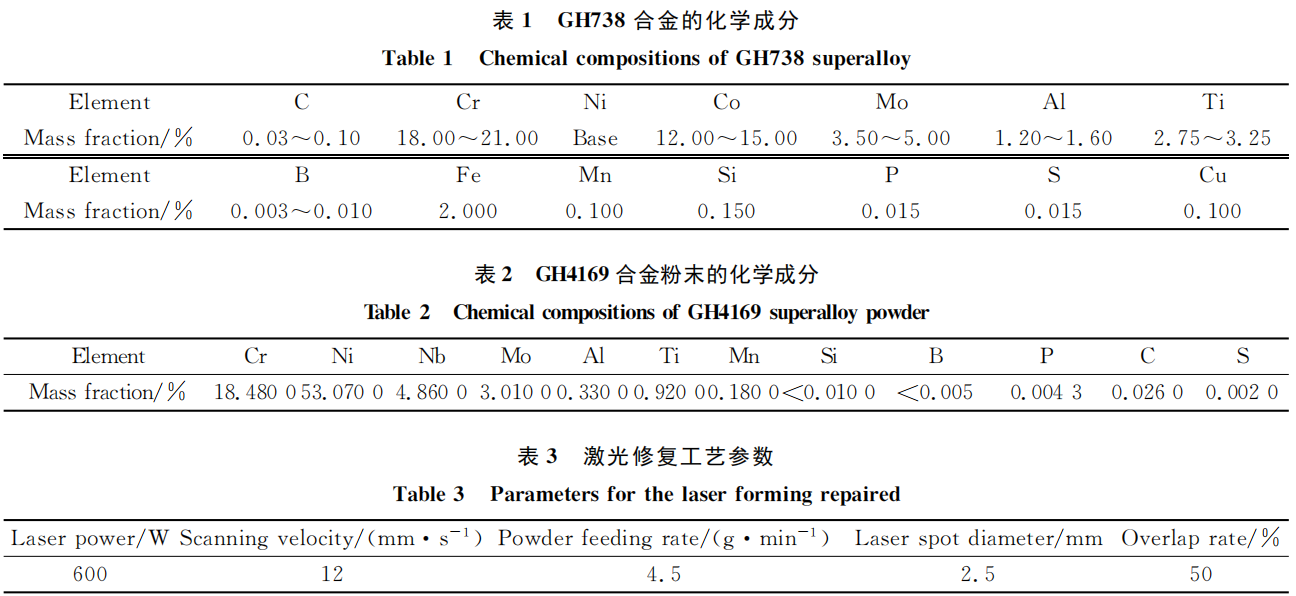

The laser repair experiments described herein were conducted using the Metal+®1005 laser additive manufacturing equipment. The substrate material selected was GH738 alloy, with chemical composition as shown in Table 1. The substrate dimensions were Φ9 mm × 2 mm. Wire cutting was employed to flatten both ends, with one end grooved. The substrate surface was coarse-ground to remove scale, exposing a fresh, bright metal surface. The substrate was then cleaned with acetone and dried. The cladding material was GH4169 powder with a particle size of 100–150 μm, whose chemical composition is shown in Table 2. The GH4169 alloy powder was dried prior to testing. The process parameters for preparing the laser-repaired GH4169/GH738 alloy specimens are listed in Table 3.

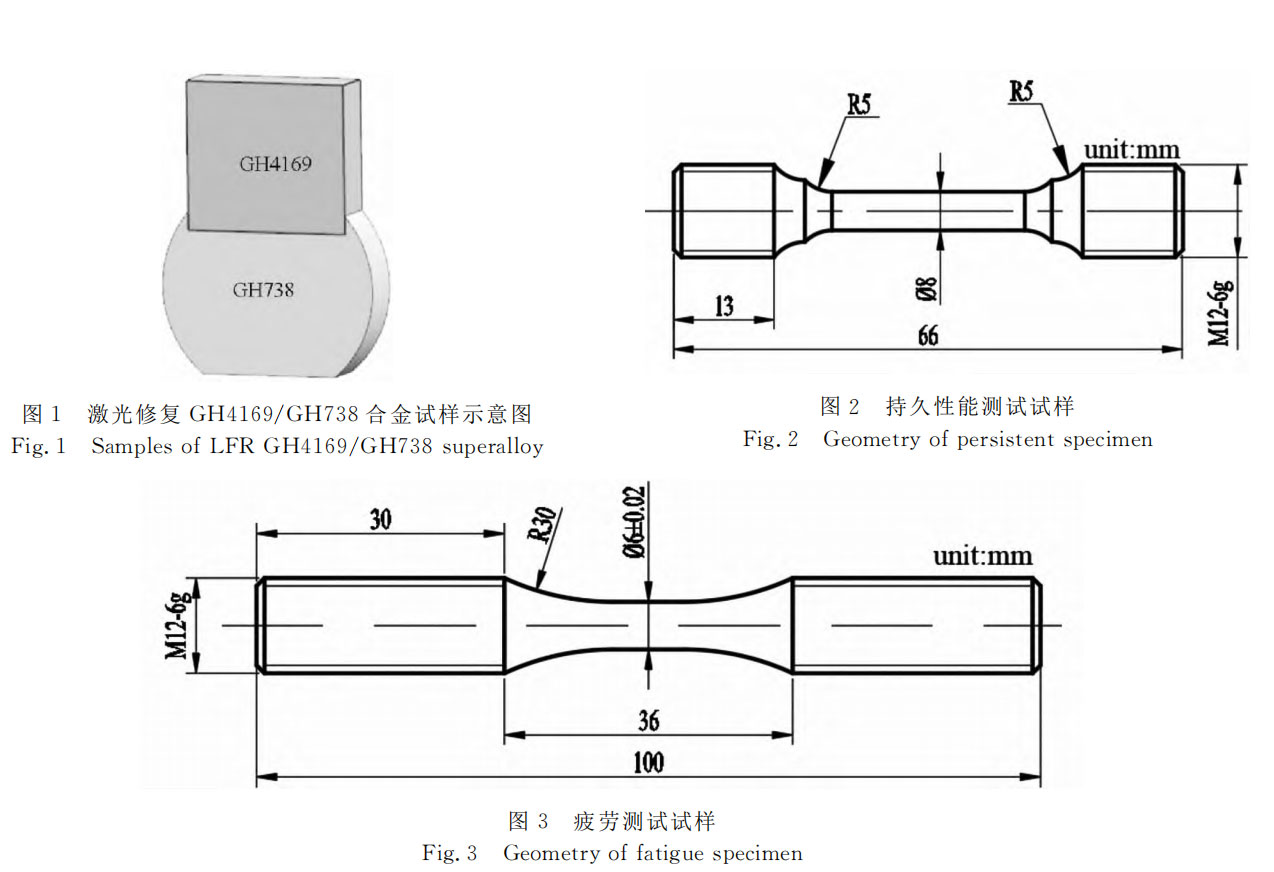

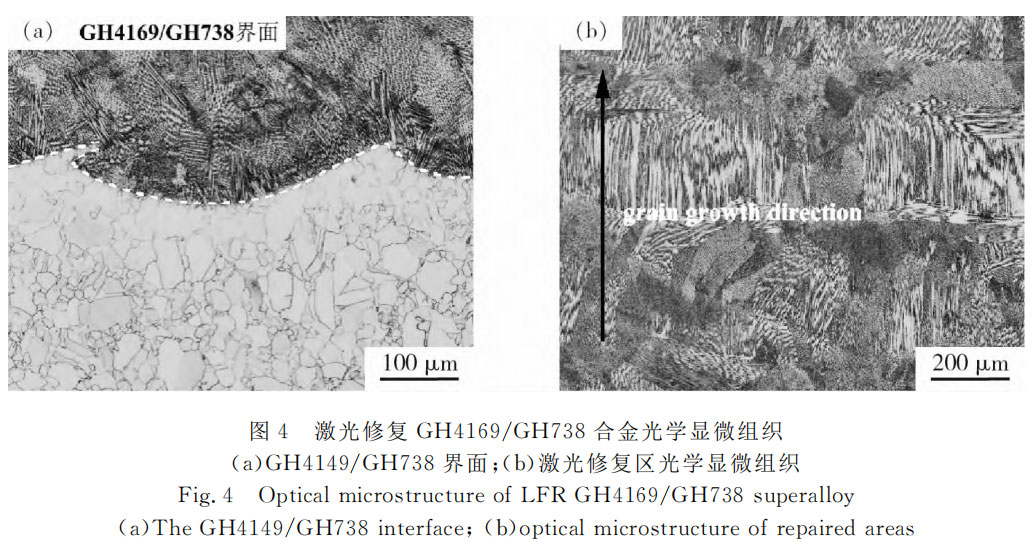

The laser-repaired specimens prepared according to the process parameters in Table 3 are shown in Figure 1. To enhance the mechanical properties of the repaired specimens, standard heat treatment for GH4169 alloy was applied: solution treatment (950°C, 1 h air cooling) followed by two-stage aging (720°C, 8 h furnace cooling to 620°C, then 8 h air cooling). The specimens underwent creep testing at 650°C under 690 MPa conditions. High-temperature creep specimens were prepared according to HB5150-1996 “Method for High-Temperature Tensile Creep Testing of Metals,” with dimensions as shown in Figure 2. The creep tests were conducted on a mechanical high-temperature creep testing machine (CTM504-A1). Low-cycle fatigue tests were performed at 455°C using a hydraulic servo fatigue testing machine (MTS370-100kN). At a cycle frequency H=0.33Hz, all specimens were cycled until fracture. High-temperature low-cycle specimens were prepared according to GB/T15248—2008 “Axial Constant-Amplitude Low-Cycle Fatigue Test Method for Metallic Materials,” with dimensions as shown in Figure 3. The etchant used for analyzing the optical microstructure was 5g FeCl₃ + 20mL HCl + 75mL C₂H₅OH.

2 Results and Discussion

2.1 Microstructure

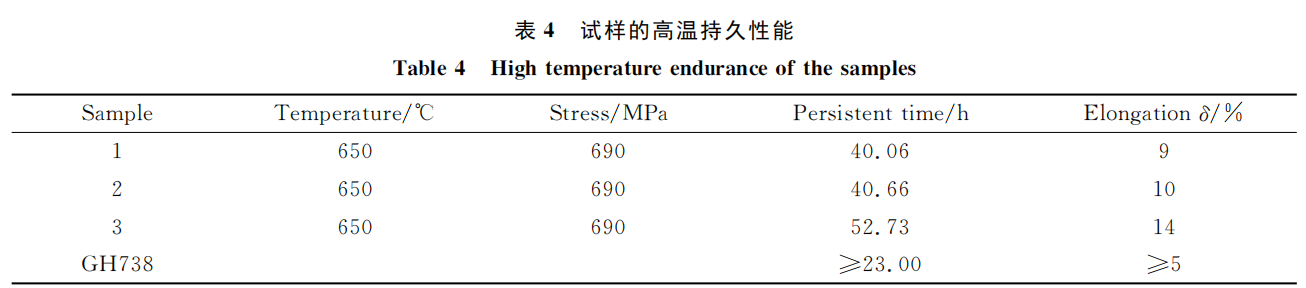

Figure 4 displays the microstructure of the laser-repaired GH4169/GH738 alloy. Figure 4(a) reveals a dense microstructure at the interface between the substrate and the repair zone (indicated by the dashed line), free from metallurgical defects such as cracks or pores, indicating a sound metallurgical bond. Figure 4(b) shows that the microstructure in the laser-repaired zone exhibits a columnar grain structure with continuous outward growth, largely parallel to the deposition direction.

2.2 Creep Performance

Three specimens were selected from the repaired samples for high-temperature creep testing. The creep fracture surfaces of all three specimens were located within the GH4169 alloy repair zone. Table 4 presents the obtained high-temperature creep test data. As shown in Table 4, the high-temperature creep performance of the repair zone specimens meets the requirements for GH738 alloy. Specimen No. 3 exhibits certain differences compared to Specimens No. 1 and No. 2. Although all specimens were prepared using the same processing method, the creep growth direction of the specimen microstructure is influenced by the laser scanning path during repair, potentially resulting in variations. Additionally, porosity and lack of fusion may occur. Although all specimens were prepared using the same processing method, differences in solidification and growth direction during laser repair resulted from variations in the laser scanning path. Additionally, defects such as porosity, lack of fusion, and unfused powder may have influenced the endurance performance.

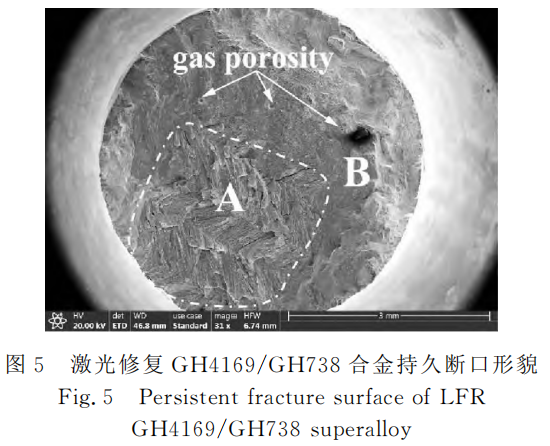

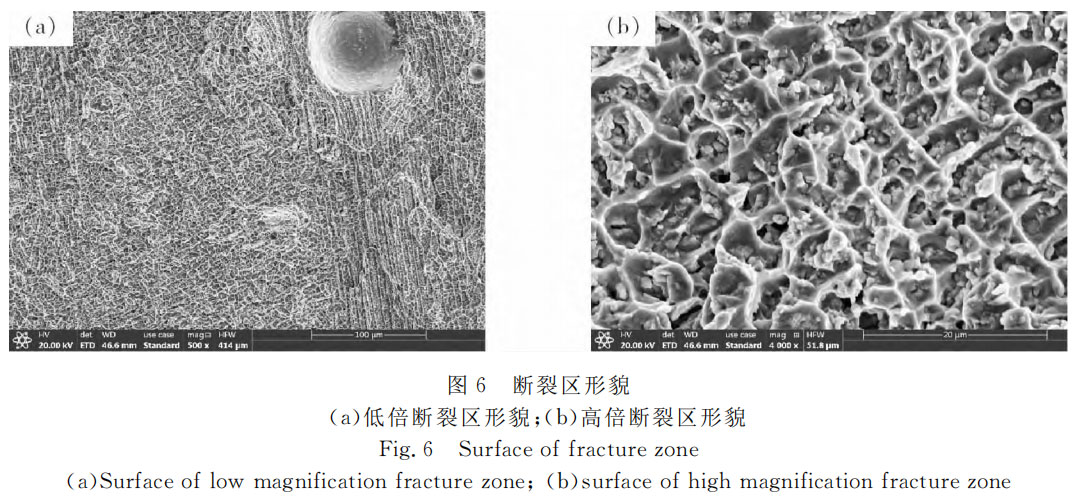

Specimen 2 was selected for analysis. Figure 5 shows the macro-morphology of the endurance fracture surface of the laser-repaired GH4169/GH738 alloy. Based on the fracture morphology, the fracture surface is divided into two regions: the crack initiation and propagation zone (Region A in Figure 5) and the final fracture zone (Region B in Figure 5). Porosity defects are present, with microcracks observed near the pores. The crack initiation zone exhibits fracture surfaces at different angles and secondary cracks. During the endurance test, cracks first originated in the crack initiation and propagation zone and then gradually propagated. As the propagating crack expanded, stress levels increased until the specimen fractured instantaneously, forming the fracture zone. Figure 6 illustrates the fracture zone morphology. Figure 6(a) reveals a mixed fracture zone exhibiting both distinct ductile pitting morphology characteristic of intergranular fracture and minor transgranular fracture. Figure 6(b) shows uniformly sized ductile pits with tearing edges on their walls, residual micro-pores, and fine particles observable within some pits.

According to the solidification process of GH4169 alloy [11]—L→γ+L→(γ+NbC)+L→γ+Laves (where L represents liquid)—the solidification of the repair melt pool using GH4169 alloy involves the formation of γ matrix phase, NbC, and Laves phase. As a brittle phase, the Laves phase promotes crack initiation and provides favorable locations for crack propagation. According to earlier studies, when the solution treatment temperature exceeds 1080°C [12], the Laves phase disappears during solution treatment. In this experiment, the solution treatment temperature was below 1080°C. At 690 MPa, as time progressed, when stress concentration at the grain boundaries reached its limit, the Laves phase separated from the grain boundaries to form microscopic voids. As adjacent voids expanded and connected, cracks propagated along the grain boundaries. Simultaneously, gas pores accelerated the crack propagation rate, ultimately resulting in intergranular fracture. Therefore, the observed differences among the three specimens can be attributed to defects as one contributing factor. In summary, the fracture behavior exhibited a mixed intergranular-intragranular ductile dimple fracture mode. The lower creep performance of Specimens 1 and 2 compared to Specimen 3 is presumed to result from porosity defects.

Due to the rapid solidification rate during laser repair forming, δ phase precipitation is scarcely observable. The precipitation temperature range for δ phase is 860–995°C [13]. Following solution treatment at 950°C for 1 hour in this experiment, a small amount of fine needle-like δ phase precipitates along grain boundaries. As a stabilizing phase in the alloy, the content, morphology, and distribution of δ phase significantly influence the notch sensitivity of the alloy. An appropriate amount of δ phase can control grain size, enhance plasticity, and coordinate the state of grain boundaries with the matching of intergranular and intragranular strengths [12]. Dual aging treatment further promotes the complete dispersion precipitation of γ′ and γ″ phases to strengthen the alloy. Therefore, it is speculated that the small particles within the toughening pits may be strengthening phases γ′ or γ″.

2.3 Fatigue Properties

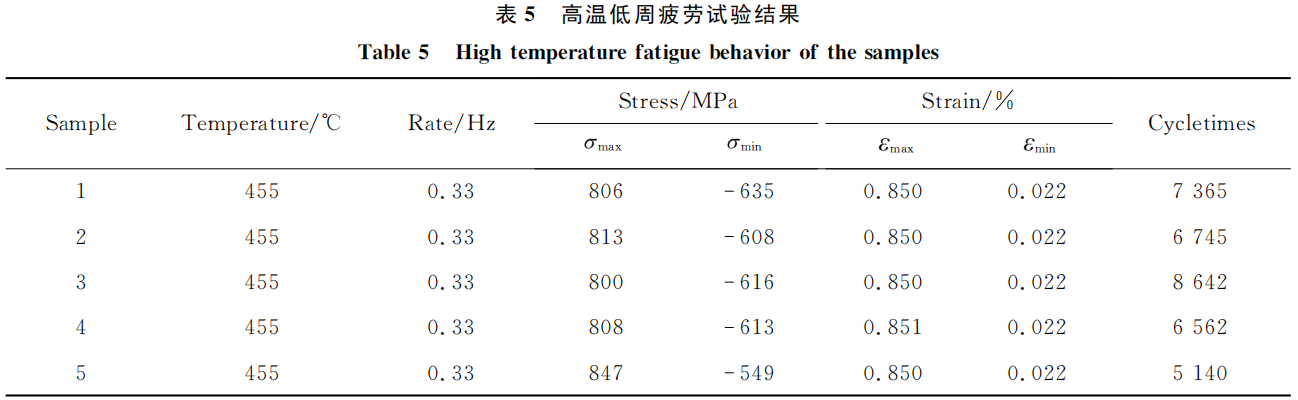

Four specimens were selected from the repaired samples for axial high-temperature low-cycle fatigue testing. All fatigue fractures occurred within the GH4169 alloy repair zone. Table 5 presents the fatigue data obtained, showing a higher number of cycles compared to spray-formed GH738 alloy. The mechanical properties of spray-formed GH738 alloy are superior to those of conventional cast-forged GH738 alloy [14]. The data in Table 5 indicate a certain degree of dispersion in the fatigue performance of the five specimens. Similarly, fatigue performance variations may arise due to the influence of laser scanning paths and metallurgical defects.

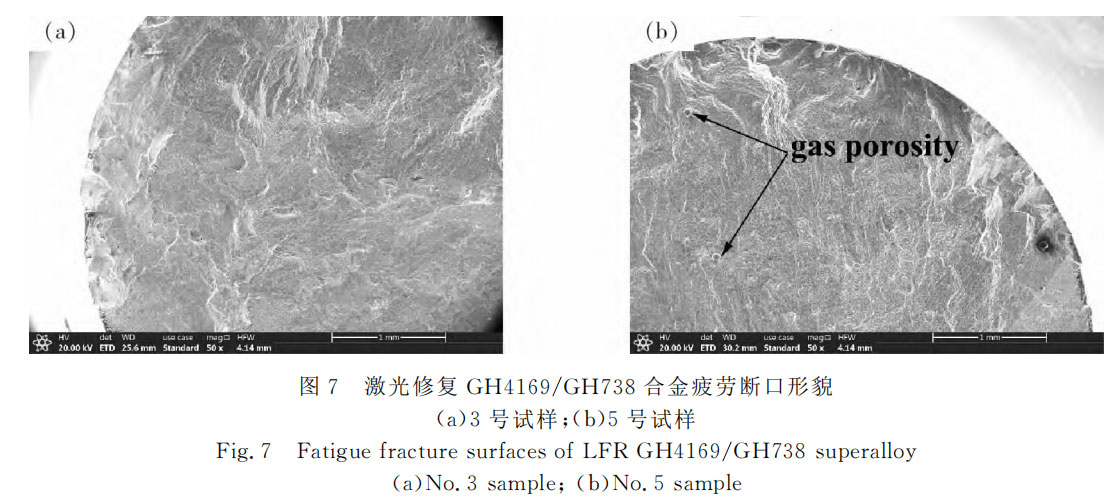

Specimens No. 3 and No. 5 were selected for analysis. Figure 7 displays the macro-morphology of fatigue fracture surfaces in laser-repaired GH4169/GH738 alloys. Fatigue failure comprises three stages: fatigue crack initiation, fatigue crack propagation, and instantaneous fracture [15-16]. Figure 7 reveals that fatigue crack initiation in the laser-repaired zone specimens all occurred at the specimen edges, with a plateau appearing at the initiation point. A river-like pattern flowing toward the specimen interior was observed at the fatigue initiation site, indicating a distinct cleavage fracture mode. Specimen No. 5 contained porosity defects internally. Cracks typically originate at slip bands, metallurgical defects, or grain boundaries on the surface. Under fatigue loading, extrusion and intrusion occur at the slip planes of the specimen, creating stress concentrations that initiate crack nucleation and form small platforms.

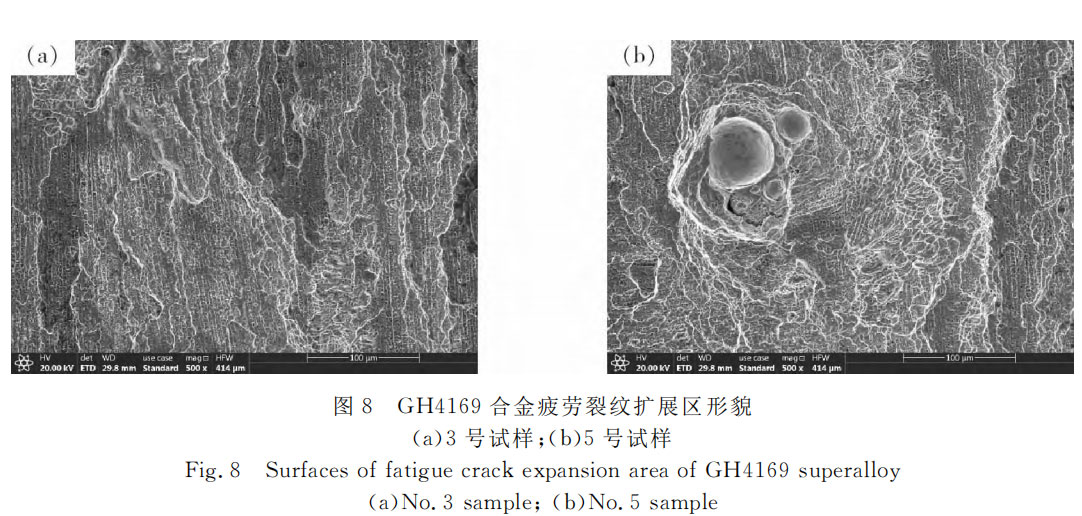

After crack initiation, the fatigue crack enters the crack propagation zone. Figure 8 shows the morphology of the fatigue crack propagation zone. Fatigue striations can be observed in the image. Fatigue striations appear nearly parallel in localized areas, while others exhibit curved or wavy patterns. When stress is minimal, the crack tip closes. As stress increases, the crack front gradually reaches maximum stress due to stress concentration, causing the crack to propagate forward and become blunted. Upon stress removal, the crack re-closes and sharpens. This cyclic process enables continuous crack advancement, forming fatigue striations. Figure 8(b) shows cracks emerging around porosity, indicating that stress concentration at defects contributes to crack initiation. Microcracks are also visible in the propagation zone. Following standard heat treatment, δ phase precipitates at grain boundaries. Under high-temperature fatigue cyclic loading, δ phase detaches, increasing crack sensitivity and creating microvoids at the interface with the matrix, which form microcracks. This indicates that intergranular propagation is the primary crack growth mechanism at this stage.

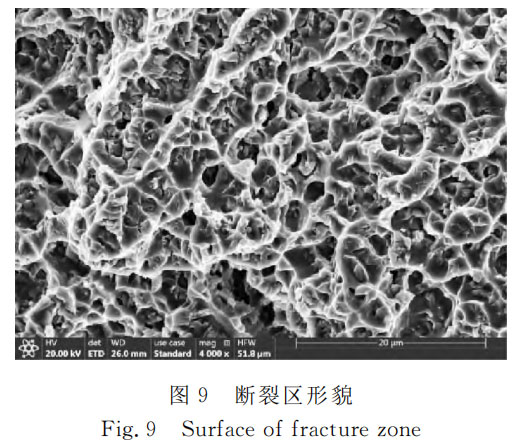

Under alternating loading, the crack continues to propagate within the propagation zone. High-temperature low-cycle fatigue transitions from the propagation zone to the instantaneous fracture zone, where the specimen undergoes intergranular ductile dimple propagation. Under stress, the specimen ultimately fractures. Figure 9 displays the microstructure of the fatigue fracture zone. The fracture zone is predominantly composed of dimples exhibiting significant shape variation and non-uniform dimensions, with bright white tear edges visible on the fracture surface. In summary, the fatigue fracture of the specimen is classified as a mixed-type fracture.

3 Conclusions

(1) The metallurgical quality at the interface of the GH4169/GH738 repair zone is excellent, with the repaired zone exhibiting a columnar grain structure that grows continuously outward.

(2) The fracture location of the laser-repaired GH4169/GH738 alloy high-temperature creep specimen occurred within the repair zone. Following laser repair and solution treatment, Laves phases precipitated at grain boundaries. Stress concentration at these grain boundaries, combined with porosity defects promoting crack propagation, led to crack growth along grain boundaries. Ultimately, fracture occurred, exhibiting a mixed intergranular-intragranular ductile dimple fracture mode.

(3) The fracture location of the laser-repaired GH4169/GH738 alloy high-temperature low-cycle fatigue specimen was within the repair zone. The crack origin was near the specimen surface and porosity, exhibiting a river-like pattern characteristic of cleavage fracture. The propagation zone contained fatigue striations indicative of intergranular fracture, forming a mixed fracture mode.

(4) The high-temperature creep and low-cycle fatigue properties of GH738 alloy repaired using GH4169 alloy powder meet the requirements for conventional cast and forged GH738 alloy. This repair method can be applied to hot-end components of GH738 alloy, providing experimental and application basis for laser repair technology of high-temperature alloy aerospace components.

Reference: Study on the Properties of Laser-Repaired GH4169/GH738 High-Temperature Alloys; Yang Xuekun1, Wang Zhong1, Yang Chunrong1, Deng Zhiqing1, Wang Zhicheng2; Vol. 43, No. 6, June 2023, Applied Laser

As a national-level high-tech enterprise, Stardust Technology develops spherical powders of rare refractory metals based on over three decades of powder research expertise. Its product portfolio encompasses tungsten, molybdenum, tantalum, niobium, and related alloys and compounds. These powders are produced using radiofrequency plasma spheroidization technology, featuring distinct core characteristics: purity generally exceeds 99.95%, oxygen content is below 300 ppm, high sphericity with smooth surfaces, absence of satellite particles and minimal hollow particles, uniform particle size distribution, excellent flowability, and stable bulk and tapped densities. Standard particle sizes range from 5 to 150 μm, with customization available per client requirements. With reliable performance, these powders suit diverse processes including laser additive manufacturing, hot isostatic pressing, and injection molding. They find extensive applications in aerospace high-temperature components, orthopedic implants for medical devices, and radiation shielding parts for defense and military industries. Our medical-grade spherical tantalum powder has achieved mass production, supporting nearly a thousand 3D-printed prosthetic replacement surgeries. Relevant products have passed third-party testing, reaching internationally leading standards. For further product details, please contact our Sales Manager, Cathie Zheng, at +86 13318326187.